Salaga Slave Market

Salaga is a place deep in the heart of the Northern Region of Ghana where

few ever make it, but it is here where a slave's journey truly began. Follow

my journey along the red roads of Northern Ghana where I trace the origins

of the Transatlantic Slave Trade and reflect on what slavery means today.

One of Ghana’s major tourist attractions is the Elmina Castle on the former Gold Coast. Built in 1482 by the Portuguese, its white-washed facade looms over the Atlantic Ocean, now an unfortunate relic of the Transatlantic Slave Trade. Twenty-five to thirty million slaves from across West and Central Africa were shipped from these shores to plantations across the seas in the Americas, Caribbean, and Europe. The Portuguese were the first Europeans to engage in the Atlantic slave trade, completing a voyage to Brazil in 1526.

However, There Is A Place Deep In The Heart Of The Northern Region Of Ghana Where Few Ever Make It, And It Is There Where A Slave’s Journey Truly Began.

You couldn’t fault anyone for not visiting Salaga. I only knew about it because I read the book ‘Lose Your Mother’ by Saidiya Hartman before I arrived. As an African American searching for her lost origins, Saidiya ended up in Salaga, where she found as little remnants of her possible heritage as I did. Though this small town really was the starting point of a great many slaves’ journeys to bondage, death, and indentured labour, there is little mention of it except for a signboard which reads, ‘Welcome to Salaga Slave Market.” The sign was erected in front of the tree where slaves were once tied and sold.

To make matters worse, it now stood in the middle of the bus station. After a couple hours drive along dusty, potholed roads, I was growing concerned that this signboard was all I had come to see. Naturally, it felt like sweet serendipity when a stranger approached me while photographing the sign. My Dagomba friend conversed with the man in Hausa, a language widely spoken in Nigeria and along West African trade routes. It seemed there was only one person in the entire town who could assist us with investigating the remains of the slave trade, and this man was willing to take us to his doorstep.

Lazing shirtless and chewing on a twig, Brazil stood in the doorway of his modest abode with a hesitant expression. In perfect English, he explained that he had just gotten home and watched TV when we arrived. I sensed that he would have rather been relaxing at the height of the midday sun, but he put a smock on anyways and asked for 5 cedis ($1.50) to fill up the tank of his motorcycle.

Brazil was born Ibrahim Iddrisu, his nickname acquired for being a great footballer in his heyday. Apart from being the unofficial gatekeeper of the rather inadequate tribute to slavery in Ghana, it was clear from the greetings he received in town that he was a man of importance. He wasn’t one for talking about personal matters, but it soon became evident that he was incredibly knowledgeable about Salaga’s role in the slave trade. As a young boy, both his grandfather and father took him through the bush around town to see what many others would have preferred to forget. We followed Brazil through dense foliage, along a barely visible footpath which opened up to a patch of semi-cleared land.

“There were once pits dug as far as the eye could see. It’s all overgrown now, but in those days, this land used to be maintained.”

The ‘pits’ he spoke of were dirt trenches where slaves were brought to be washed and oiled with shea butter before being taken to the central market in town. Not far from the earthen holes were a smattering of water wells where the water was fetched from. Brazil said that this sweet water was the purest in town even today and insisted that we taste it.

As we explored the grounds where thousands, if not millions of captive Africans, had passed, I just couldn’t understand why Salaga? Brazil explained, “Salaga is the centre of Ghana. There are roads in all directions, and slaves were brought here, not just from other regions but also from all of the countries surrounding us. You see, Salaga was once an important market town in the trade for kola.

As we stood over the blue pools of well water, Brazil recounted how African American tourists often came in large numbers, falling down in tears at the stone archway before washing themselves in the water. They came looking for some thread of their origin, only to find themselves in a place that barely associates itself with its own involvement in their loss of identity. I could understand why; in the Americas, Black people are likely the victims’ descendants, but here in Salaga, their ancestors are more than probably those who enslaved them.

In ‘Lose Your Mother’ Hartman recounts how Ghanaians often regarded her as ‘one of the lucky ones.’ Rather than be the successor of a slave or a slaver in Africa, she had made it to America. One couldn’t fault them for feeling this way—life in the Northern Region’s hinterlands had little scope for progress.

Before we proceeded onwards on our impromptu tour, Brazil turned to me with a solemn expression on his face, “My sister, you know, it was not only your people who enslaved ours. It was we Africans who started the slave trade and sold our own people to the Europeans.”

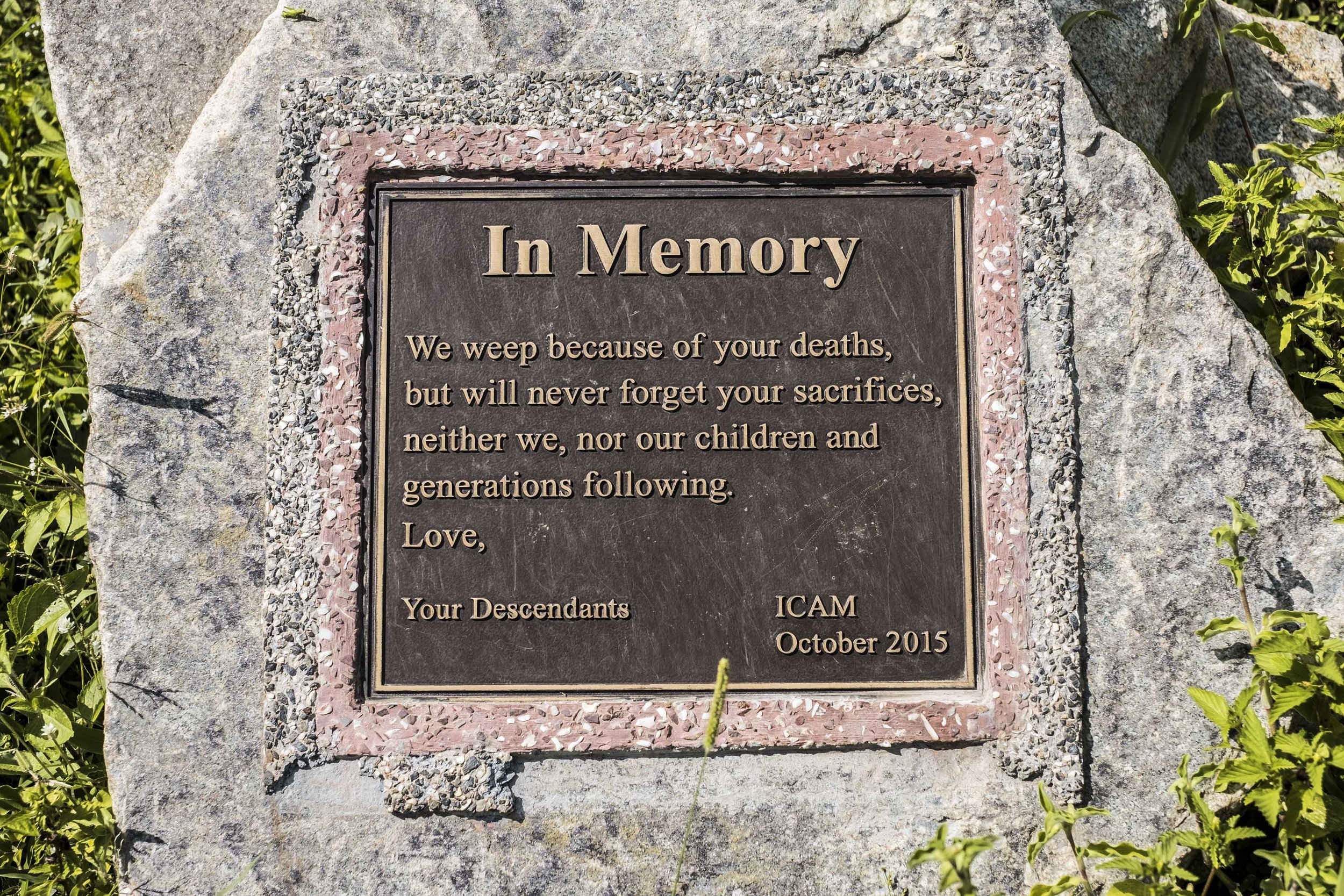

Our motorcycles weaved through a cluster of mud houses and giant baobabs until we stopped at a field. The smell of feces was overwhelming. Ten steps into the patch of green, a stone plaque had been erected atop a mass gravesite by an African American pastor. It read,

The Salaga museum was our final destination. Brazil had guided us in a perfect circle and brought us back to the town center to a beautiful shaded courtyard where well-dressed men congregated to gamble. We waited for someone with the keys to come and open the museum door, which housed a pathetic collection of rusty spears, shackles, and calabash. The floor was covered with a thick layer of sand, probably leftover from the previous Harmattan (season of dusty trade winds from the Sahara). Here, Brazil took his leave. With a couple of handshakes and a humble tip, we bid him and our journey through the slave trade of Salaga farewell.

Following an unsavoury lunch at an adjacent restaurant, I rode back to Tamale with an unsettled feeling. The slave trade, which tortured, displaced, and erased so many Africans, seemed all but forgotten in Salaga. For a sinister history that lasted roughly 500 years and broke families, traditions, and ancestral lineages, it supported my sense that slavery is not so much history as we’d like to believe.

There are currently believed to be 21 million slaves worldwide. It is simply not enough to point an accusing finger at the horrors of human history; we must collectively acknowledge that slavery is an enduring dimension of the human experience. To eradicate this evil, we can blame and march in protest, or shout to the heavens in our loudest cries, but we must also be mindful of what we consume and who has been exploited to allow for our consumption. We should acknowledge our own compliance every time we use our cell phones, admitting that its conflict minerals were likely mined by an indentured African labourer. And that tiresome immigrant trying to sell us sunglasses while we drink our cappuccino in a European plaza? They, too, may have narrowly escaped a life of slavery only to find themselves in a different kind of bondage.

If the source of slavery is ever to be totally understood, then we must admit the truth in the words of W. E. B. Du Bois, “Most men today cannot conceive of a freedom that does not involve somebody’s slavery.”